In January 2011, Twitter posted a message in its blog, stating that “there are Tweets that we do remove, such as illegal Tweets and spam. However, we make efforts to keep these exceptions narrow (…) and we strive not to remove Tweets on the basis of their content.”

One year later, another post announced a major change: Twitter has now the ability to filter – or withhold, using its vocabulary – Tweets’ content, as well as individual accounts, in order to conform to the demands of specific countries. The declaration provoked a harsh reaction among users from all over the world, and last January 28 some Twitterers silenced their Tweets as a way of expressing their opposition to Twitter’s plan, using the hashtag #TwitterBlackout.

Many analysts saw Twitter’s move as a way to enter the Chinese market, in which the social network is completely blocked, together with Facebook and You Tube. But which are the exact implications of Twitter’s new policy? Is it really aimed at jumping into the world’s biggest Internet market? Will it succeed?

Panta Rei: Tweets must flow

Reactions to Twitter’s decision have been diverse, but the majority of them were of profound discontent and disapproval. Editorials with titles like “Twitter Commits Social Suicide”, or “The Internet welcomes a new censor: Twitter!” appeared in the press worldwide; Ai Weiwei, the most famous Chinese artist and prolific Twitterer, declared his intention to stop using it.

However, the company explained that what is perceived to be a censorship tout court is actually an attempt to protect the site’s integrity. Indeed, Twitter has always censored some contents –the company’s CEO Dick Costolo claimed: France or Germany, for example, restrict certain pro-Nazi contents. Until now, Twitter had to remove banned contents globally in order to take account of those countries’ requests. From now on, this content will be blocked only in those countries, while it will be available for the rest of the world. So technically, with this country-by-country approach, Twitter is actually loosing its censorship policy.

Furthermore, the company has promised to be transparent with regard to removed contents and censorship requests. Affected users will see explanatory messages on their screen, and they will have access to the reporter’s complaint along with instructions on how to file a counter-notice. Twitter has also promised to strengthen its collaboration with Chilling Effects, a non-profit project focused on issues of free speech online. So, if at the one hand Twitter will effectively censor Tweets’ contents under governments’ requests, at the other hand it does commit itself to take some steps to mitigate this decision, the most important of which is transparency.

Google: a bad example?

The controversy that aroused around Twitter reminds somehow the one that followed Google’s decision to comply with Chinese censorship laws. Google first opened for business in China in 2005, but after announcing that it had been hacked by the government, the company said it would no longer censor its search results and moved its operations to Hong Kong. But at the start of 2006, it launched google.cn, which is subject to the Chinese Great Firewall.

The official reason to come back to China was that Google wanted to make information universally accessible, by offering its search services to a fifth of the world’s population; however, recent Wikileaks revealed that a second reason for that was the particular Chinese internet structure – that is, there is only one internet gateway into China. Thus, as a condition of being allowed to host its services within China – and in order to be able to compete with the biggest Chinese search engine, Baidu – Google agreed to censor itself its search results. In fact, as Clive Thomson explained, since the Chinese government would have never provided detailed information about which sites to block, Google came up with a high-tech solution: they set up a computer inside China and programmed it to try to access Webpages outside the country. If a site was blocked by the firewall, it became part of Google’s blacklist, and it began to censor it. The Google executives never formally sat down with the government officials and received permission to put the disclaimer on censored search results. They simply decided to do it in order to keep a foot in China.

Google, who defines itself as an “ethical company” whose motto is “Don’t be evil”, faced many critics both from human rights activists and from the government of the US after this decision. Moreover, the Chinese politburo continued harassing the American company in many ways, such as launching various cyber attacks on a regular basis in 2009-2010, disrupting its Gmail service and subjecting Google to tax investigation in 2011.

Unlike Google, Twitter will remove contents only when required, in response to a valid legal request, on a case-by-case basis, rather than auto-filtering them. This proactive approach is described as key in order to respect users’ freedom of speech: “Twitter does not mediate content, and we do not proactively monitor Tweets.”

The little Chinese brother has grown up: Weibo

Even if Twitter is blocked in China, China has taken to micro-blogging like no other country. Sina Weibo, the Chinese Twitter, has recently reached 250 million users, doubling Twitter users, and growing at a rate of about 10 million a month, although there are many miles of fake, duplicate and spam accounts on Weibo.

Weibo is often defined as “Twitter with Chinese characteristics.” Those characteristics include a fragile equilibrium between government interference and free speech. Weibo certainly respects the authorities dictates over censorship; nevertheless, Chinese users created a new and rapidly evolving language of abbreviations, neologisms, and substitute words that allow them a certain degree of liberty in typing.

Weibo’s monopoly in China could be jeopardized by Twitter, Facebook and Google+, which have conquered the rest of the world. Therefore, there is also a strong protectionist factor that affects the Chinese government’s decision to leave thesesocial networks out of the country. But the question is not only whether Twitter or Facebook will eventually go to China. The real question is whether Weibo can challenge their influence by expanding its operations outside China. Few months after its English version was released in April 2011, Weibo captured 450,000 users in the U.S., the Wall Street Journal reports, among whom there are many celebrities. Observing the current trends, this number is likely to keep on growing.

Twitter´s trick or treat

The Chinese government recently endorsed Twitter’s new policy through its official newspaper. Still, it is not sure whether the American company will finally enter the Chinese market, and – if it does – whether it will succeed in beating a great competitor such as Weibo.

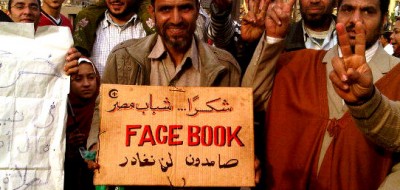

The company finds itself in tension between corporate ethics and market rules. At the one hand, without any modification of its policy it would not have any possibility to accede the greatest Internet market of the world. At the other hand, a bad move could undermine Twitter’s reputation among global users, which consider it as a symbol of freedom of expression, even more after the Arab Spring. But as Google has shown, for an internet company who wish to expand itself, it is compelling to deal with censorship, not only the Chinese one. Indeed, this new policy might be very useful now that the company has launched its versions in Arabic, Farsi, Hebrew and Urdu. Twitter’s strategy should be considered from a pragmatic point of view: in business world, the primary goal is profit. But there are many ways to get there. Twitter is on an exploring-mode; whether it went in the right or the wrong direction, Twitterers’ Tweets will tell.

This is a non-profit explanation.