Between April 2 and June 14 1982, exactly 30 years ago, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, leading to a short but bloody war between Argentina and the United Kingdom over sovereignty over this famous archipelago, located 300 miles off the coast of Argentina in the South Atlantic Ocean. The fighting lasted barely three months, from the invasion of the Islands by the Argentinian forces, who entered the capital Port Stanley, until Britain subsequently reconquered the territory. However, the number of casualties was high (650 Argentinian servicemen and 255 British, along with three Falklands civilians) and the conflict led to important political consequences for both countries: mainly, Argentinian President Leopoldo Galtieri resigning as leader of the country’s military junta, and the re-election of the ‘Iron Lady’, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The two-century conflict came to a head with this episode of violence and continues into the present.

On June 12 2012, the Falkland Islands government decided to counter Argentinian sovereignty claims by scheduling a self-determination referendum for the first semester of 2013, thus deciding on the status of the islands. The two countries involved in the conflict did not take long to react, but before we studying these, let us look take a brief look back at the history of this conflict.

Key facts about the historical dispute

The Falkland Islands are said to have been first sighted in the 1500s. Before 1800, France, Britain and Spain subsequently established settlements on the isles, but they were abandoned after several disputes. In 1820, Argentina, having recently gained independence from the Spanish Crown, took possession of the territory and in 1829 declared it had “political and military command of the Malvinas”.

![Malvinas - la ubicación [Atlas universel de geographie ancienne et moderne; Wikimedia Commons]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/Lapie1833-Malvinas.jpg) However, Argentina’s era of control was quite short, since in 1833, British forces disembarked on the islands with the aim of “reasserting British sovereignty”, declaring the Falkland Islands (the name that was assigned to the territory) a colony of the British Empire. The islands remained under their control ever since and for 149 years to follow, Argentina continually considered the United Kingdom an invading power, and the Falkland Islands, or the Malvinas, an “integral and indivisible part of its territory, occupied illegally”.

However, Argentina’s era of control was quite short, since in 1833, British forces disembarked on the islands with the aim of “reasserting British sovereignty”, declaring the Falkland Islands (the name that was assigned to the territory) a colony of the British Empire. The islands remained under their control ever since and for 149 years to follow, Argentina continually considered the United Kingdom an invading power, and the Falkland Islands, or the Malvinas, an “integral and indivisible part of its territory, occupied illegally”.

In 1960, a UN General Assembly resolution proclaimed the need to bring colonialism to an end. Initially, Great Britain vowed to relinquish all of its colonial possessions overseas, including the Falkland Islands. Nevertheless, with the passing of time, this promise went unfulfilled, and the UN called on both countries to negotiate a solution, which they have not done, to date. Until this solution comes about, the islands maintain their status as a disputed ‘non self-governing territory’.

In 1982, Argentina’s military junta decided to resolve the issue in a quite straightforward way, invading the islands to in order to swing the balance of sovereignty. However, in addition to encountering the British military resistance, Argentina was condemned by the international community, which considered the episode an assault (note, nevertheless, that the majority of Latin American countries supported the Argentinian cause).

The conflict today

On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the war, the Argentinian president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner addressed the UN at the headquarters in New York, in order to put some pressure on the United Kingdom to start negotiations. The plea for these negotiations, as mentioned earlier, is backed by several resolutions adopted by the UN Decolonisation Committee.

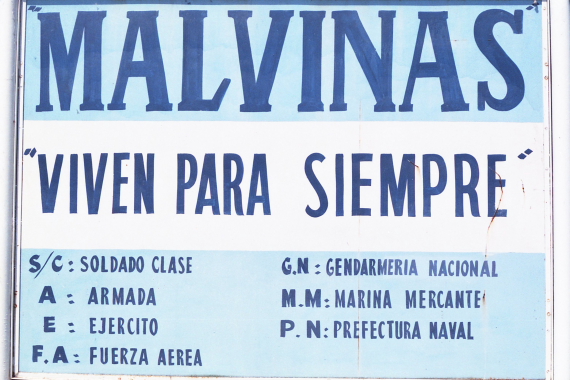

![Guerra de Malvinas [Author: alefot, Flickr Account]](http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7047/6953909513_6a2bcd60c4_m.jpg) The president is aware that Argentina’s historic claim of the archipelago is deeply rooted in popular culture of her country and that it is a very sensitive matter for most of its citizens. Additionally, she is undoubtedly aware of the political interests of reviving the claims to the Falkland Islands at a time when her popularity levels seem to have dropped. Unhappy with how her address at the UN was received, Fernández de Kirchner seized her chance at the G20 summit in Los Cabos (Mexico) last month, ambushing UK Prime Minister David Cameron in order to give him an envelope containing UN resolutions on the Falklands issue. Cameron responded to the ambush saying the Falklands residents’ views should be respected, and declined the Argentinian offer.

The president is aware that Argentina’s historic claim of the archipelago is deeply rooted in popular culture of her country and that it is a very sensitive matter for most of its citizens. Additionally, she is undoubtedly aware of the political interests of reviving the claims to the Falkland Islands at a time when her popularity levels seem to have dropped. Unhappy with how her address at the UN was received, Fernández de Kirchner seized her chance at the G20 summit in Los Cabos (Mexico) last month, ambushing UK Prime Minister David Cameron in order to give him an envelope containing UN resolutions on the Falklands issue. Cameron responded to the ambush saying the Falklands residents’ views should be respected, and declined the Argentinian offer.

While the Argentinian government is trying to attract media attention to the conflict in order to bring the British to the negotiation table, the latter seek to avoid discussions at all costs, fearing a debate on the status quo and inevitable loss of sovereignty over the islands, provided the UN takes a stand in favour of Argentina. In its intent to silence any attempt at debate, the British government has lent its support to the initiative of the Falkland Islands government to hold a referendum on the status of the islands in 2013, with a fairly predictable result (the vast majority will opt to remain under British administration).

![Falkland Islands topographic map [Wikimedia Commons]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/Falkland_Islands_topographic_map-en.svg/500px-Falkland_Islands_topographic_map-en.svg.png) Such, at least, this is the desire of the islands’ governors. Gavin Short, chairman of the islands’ legislative assembly, stated they were holding the referendum “to show the world just how certain we are about it [our future]” (i.e., the intention to remain under British administration).

Such, at least, this is the desire of the islands’ governors. Gavin Short, chairman of the islands’ legislative assembly, stated they were holding the referendum “to show the world just how certain we are about it [our future]” (i.e., the intention to remain under British administration).

In the meantime, the Argentinian government has categorically rejected the referendum, considering it invalid, since the islands were artificially occupied by settlers of British origin (presently the islands are home to approximately 3000 inhabitants, mostly British citizens).

Decolonization, the ongoing process

The dispute over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands/ the Malvinas puts a spotlight on a more global problem: the remaining colonial holdouts in the world – 16 non-self-governing territories, according to the UN, to be exact. The old Western empires, led by Britain, cling to their overseas possessions, which they inherited, and which stand for what they once were, in the glorious past.

On the other hand, the emerging and increasingly democratic powers, including Argentina, do not accept their relegation to the fringes of the international forums. They are claiming their piece of pie in the international pecking order, especially at the time when the European powers, longtime chieftains in the international power arena, are in full retreat.

Translation of the original article in Spanish by Victoria Shevela.

This is a nonprofit explanation.